Consent

Consent laws vary by jurisdiction and over time. Currently, there is move away from basing consent laws on a clear refusal (no means no) and toward affirmative consent or enthusiastic consent. While consent laws are written in a gender-neutral manner they are always applied in a gendered manner. The focus is always on female consent with male consent ignored or presumed to always be present.

Withdrawal of Consent

It is now established in law in virtually all jurisdictions that consent to sex can be withdrawn at any time. This should be considered when understanding the implications of affirmative consent below.

No Means No

This has been the prevailing form of consent in many societies during the modern era. Using this standard consent is clearly withdrawn when one participant makes a clear statement or gesture (such as forcefully pulling away) which indicates consent has been withdrawn. Continuing to engage in sexual activity after consent has been withdrawn could constitute sexual assault. This level of consent was characterised in the western world through advertising campaigns revolving around the phrase Which part of no don't you understand?.

Notably Western courts grant a person very little time in which to cease sexual activity following withdrawal of consent. Maouloud Baby was convicted of rape in the United States after a woman alleged that he continued sexual intercourse with her for five seconds after she withdrew consent. Maouloud Baby was a minor at the time. Kevin Ibbs was convicted of rape in Australia after a woman alleged that he continued sexual intercourse with her for around 30 seconds after she withdrew consent.

No means no is increasingly being replaced in Western nations by affirmative and enthusiastic consent, which are better characterised as yes means yes.

Affirmative Consent

Consent laws around the world are moving towards affirmative consent in which the onus of proof is on the accused. While affirmative consent regulations and laws are written in a gender-neutral manner they are always applied in a gendered manner where it is presumed that the man continues to provide consent and that it is only the consent of the woman that needs to be considered. The remainder of this section will be phrased in the manner that regulations and laws are applied.

In an affirmative consent jurisdiction, a woman engaging in sex with a man need not notify the man when she withdraws consent. Rather it is presumed that the man needs to take note of her affirmation of consent (verbally or otherwise) and cease sexual activity if he does not observe it. This shifts the onus of proof to a man accused of sexual assault as it is now up to the man to establish that the woman did not withdraw consent.

In an affirmative consent jurisdiction consent to sex can be withdrawn by a woman at any time without notice. A man seeking to defend himself against an allegation of sexual assault in an affirmative consent jurisdiction would need to establish to the court that the woman had consented to sex continuously. It is unrealistic to presume that a man could offer sufficient evidence to establish continuous consent. Men who have sex with women in affirmative consent jurisdictions are opening themselves up to the risk of future prosecution. It should also be considered that most jurisdictions have no statute of limitations on criminal matters, meaning a man may be expected to show a woman consented to sex decades after the event.

Consent can be withdrawn at any time so affirmative consent has to be continuous to have any value. If the woman stops consenting affirmatively the man must cease all sexual activity or he could go to jail.

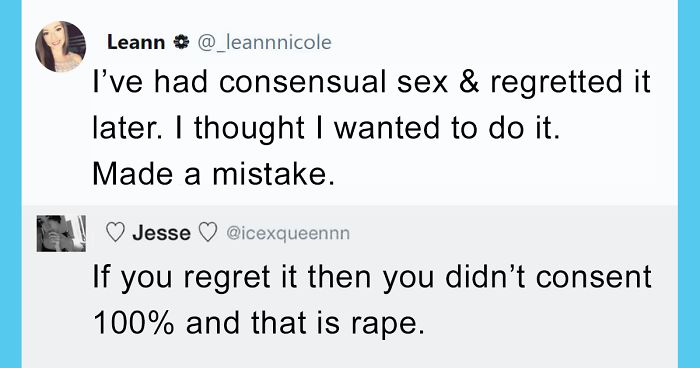

The inherent flaw in affirmative consent is that consent or the lack thereof exists only in the mind of the accuser. The courts can never truly know what was in the mind of the accuser at the time they assert they were sexually assaulted. There is a legal principle that says that intent is established from actions. Affirmative consent, however, requires no actions on the part of the accuser so it is impossible to establish a lack of consent. The accuser could be engaging in no action and yet still be consenting. The courts can establish that consent was granted but they can never establish that it wasn't granted. Thus the assertion of lack of consent on the part of the accuser becomes unfalsifiable.

Enthusiastic Consent

Enthusiastic consent is similar to affirmative consent but goes beyond merely affirming consent. Now consent must be enthusiastically given.

Deception

New York state is considering introducing laws that would make it a crime to be less than fully truthful with sex partners. So a man lying about his social status or job would find himself charged as a result of having sex with a woman without consent.[2]

Jurisdictions

Australia

Queensland

Feminists have consistently and widely claimed that affirmative consent will not move the onus of proof to the accused. Despite this the Queensland government has admitted considering moving the onus of proof to the accused under proposed changes to concent laws.[3]

Onus of proof and the excuse of mistake of fact

[58] A fundamental principle is that the onus of proof in criminal proceedings rests with the prosecution. For an offence of rape or sexual assault, the prosecution must prove every element of the offence, beyond reasonable doubt. Further, if mistake of fact as to consent is raised on the evidence, the prosecution must prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the defendant did not honestly believe that the complainant gave consent or that any such belief was not reasonably held.

[59] The Commission has carefully considered the arguments for and against reversing the onus of proof for the excuse of mistake of fact onto a defendant charged with an offence under Chapter 32 of the Criminal Code. It has concluded that there is no adequate justification for reversing the onus of proof. The interests of justice are best served by maintaining the status quo, which in the Commission’s view strikes the right balance between the rights of the individual and the wider interests of the community. [4]

Submissions—opposition

5.35 The Queensland Council for Civil Liberties similarly noted that a legislative model that requires affirmative consent fails ‘to adequately recognise the deep subjectivity and diversity of human sexual experience’.

5.36 That respondent submitted that creating an affirmative consent model would involve a practical reversal of the onus of proof. This, it was submitted, would particularly be the case if legislation were introduced requiring the person seeking to engage in sexual activity to take steps to ascertain consent. [5]

The Queensland government admits that no Common Law jurisdiction has enacted affirmative consent.

CLEAR AND UNEQUIVOCAL ‘YES’

5.47 This option would require consent to be communicated by a clear and unequivocal ‘yes’.

5.48 A reform of this nature would be unique both in Australia and in other jurisdictions that have similar sexual assault provisions.

New South Wales

On the 25th of May 2021 the New South Wales (NSW) state government announced their intention to introduce affirmative consent laws.[6] A proposal to introduce a phone app for consent drew criticism on the basis that consent can be withdrawn at any time.[7]

The New South Wales (NSW) Law society recommended only minor changes to the definition of consent and considered an affirmative consent definition undesirable.[8][9] The NSW Council for Civil Liberties raised concerns about the new laws.[10]

These legislative changes were originally proposed following the acquittal of Luke Lazarus.

“If you want to engage in sexual activity with someone, then you need to do or say something to find out if they want to have sex with you too – it’s that simple,” NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman said. [11]

If this law only applies before sexual activity begins, as the Attorney General claims here, then it does nothing to change the definition of consent.

If it is continuous, which is what it would need to be to actually be affirmative consent, then agreement before beginning does nothing to establish continuous consent.

Victoria

Feminists have recently claimed that Victoria has had affirmative consent for years.[12] This is true but the state has made legislative changes that have moved it towards affirmative consent.[13]

A recent study on rape trials in Victoria noted:

"Legislative reform in Victoria has moved towards an affirmative consent standard, requiring active communication by all parties to a sexual act. Such a standard should safeguard against narratives of force and resistance in rape trials, and place the onus on the accused to establish consent." [14]

Sweden

Sweden has an offence known as negligent rape in which the accused can be convicted because they did not properly establish consent even though all parties admit they did not intend to rape.[15] This appears to be genuine use of affirmative consent in law.

Summary

The key points of this article are:

- Men should seriously consider the ramification of sex with women in affirmative or enthusiastic consent jurisdictions

- Affirmative or enthusiastic consent shifts the onus of proof to the accused

- Affirmative and enthusiastic consent laws and rules are always applied in a gendered manner

- There is no statute of limitations on criminal offences in many jurisdictions

- If someone is accused of sexual assault and immediately makes the same complaint against their accuser, both could be convicted.

A man could have sex with a woman and have her accuse him of rape 30 years later only to find that he has to prove she enthusiastically consented to the sex to clear his name. It's nearly impossible to prove this at the time, but would likely be impossible decades later.

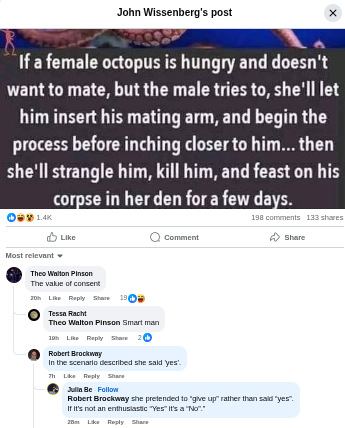

Applied to Animals

Next Steps

Feminists are now starting to argue that consent should be irrelevant and that rape should be redefined so that it can be established on the basis of power dynamics.[17]

External Links

- Dear Prudence

- Penn State Retroactively Redefined Consent after Accused Student Won A New Hearing Lawsuit

- Man charged after kissing woman live on TV

- Consent, it's a piece of cake

- Consent can be withdrawn at any time

- Tasmania is the only jurisdiction in which there is no consent in the absence of verbal or physical communication as to free agreement

- Consent-as-a-felt-sense

- Enthusiastic consent

- University of Queensland Law Journal

- Queensland Legal Aid Handbook

- NSW consent laws to be reviewed

- In Win for Due Process, American Bar Association Voted Against Affirmative Consent

- NSW, Australia

- Tasmania, Australia

- Discussion of proposed legislative changes in NSW

- Consent in the UK

- Public Radio International talking about Sweden

- Discussion - Crimes Legislation Amendment (Sexual Consent Reforms) Bill 2021

References

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/groups/journalofscientificshitposting/posts/4149439185270086/?comment_id=4149545441926127&reply_comment_id=4150265951854076¬if_id=1766324313561371¬if_t=group_comment_mention

- ↑ https://reason.com/2021/04/08/deceiving-your-sex-partner-would-be-a-crime-under-bill-backed-by-new-york-democrats/

- ↑ https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Documents/TableOffice/TabledPapers/2020/5620T1217.pdf

- ↑ https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Documents/TableOffice/TabledPapers/2020/5620T1217.pdf

- ↑ https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Documents/TableOffice/TabledPapers/2020/5620T1217.pdf

- ↑ https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-25/nsw-unveils-sweeping-changes-to-sexual-assault-laws/100162870

- ↑ https://www.mondaq.com/australia/crime/1095672/sexual-consent-law-reform-in-nsw-a-nods-as-good-as-a-wink-on-a-blind-date

- ↑ https://tinyurl.com/4pvvvzt5

- ↑ https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3432850

- ↑ https://www.nswccl.org.au/affirmative_consent

- ↑ https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/relationships/nsw-parliament-passes-affirmative-consent-laws/news-story/86303ae2013edae014e9b4e194caeac7

- ↑ https://archive.is/wip/CCEAg

- ↑ https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/persistent-narratives-of-force-and-resistance-affirmative-consent

- ↑ https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/persistent-narratives-of-force-and-resistance-affirmative-consent

- ↑ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sweden-crime-rape-law-trfn-idUSKBN23T2R3

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/groups/journalofscientificshitposting/posts/4149439185270086/?comment_id=4149545441926127&reply_comment_id=4150265951854076¬if_id=1766324313561371¬if_t=group_comment_mention

- ↑ https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/content/event/rape-redefined-catharine-mackinnon-conversation-kate-oregan