Seneca Falls Convention: Difference between revisions

Partial import from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178 |

No edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

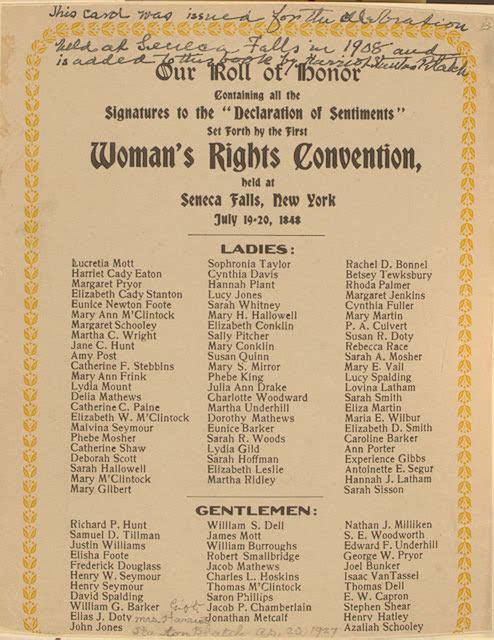

[[File:Woman's_Rights_Convention.jpg|thumb|Signatories to the [[Declaration of Sentiments]] at the Seneca Falls Convention, 1848.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention |

||

| ⚫ | The [[Seneca Falls Convention]] was the first women's rights convention and is today generally considered to be the origin of feminism by both [[feminists]] and [[anti-feminist]]s, although the word itself was coined by [[Charles Fourier]] in 1837. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman". Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the town of Seneca Falls, New York, it spanned two days over July 19–20, 1848. Attracting widespread attention, it was soon followed by other women's rights conventions, including the Rochester Women's Rights Convention in Rochester, New York, two weeks later. In 1850 the first in a series of annual National Women's Rights Conventions met in Worcester, Massachusetts.<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Female Quakers local to the area organized the meeting along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was not a Quaker. They planned the event during a visit to the area by Philadelphia-based Lucretia Mott. Mott, a Quaker, was famous for her oratorical ability |

||

| ⚫ | Female Quakers local to the area organized the meeting along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was not a Quaker. They planned the event during a visit to the area by Philadelphia-based Lucretia Mott. Mott, a Quaker, was famous for her oratorical ability.<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The meeting comprised six sessions including a lecture on law, a humorous presentation, and multiple discussions about the role of women in society. Stanton and the Quaker women presented two prepared documents, the Declaration of Sentiments and an accompanying list of resolutions, to be debated and modified before being put forward for signatures. A heated debate sprang up regarding women's right to vote, with many – including Mott – urging the removal of this concept, but Frederick Douglass, who was the convention's sole African American attendee, argued eloquently for its inclusion, and the suffrage resolution was retained. Exactly 100 of approximately 300 attendees signed the document, mostly women. |

||

| ⚫ | The meeting comprised six sessions including a lecture on law, a humorous presentation, and multiple discussions about the role of women in society. Stanton and the Quaker women presented two prepared documents, the [[Declaration of Sentiments]] and an accompanying list of resolutions, to be debated and modified before being put forward for signatures. A heated debate sprang up regarding women's right to vote, with many – including Mott – urging the removal of this concept, but [[Frederick Douglass]], who was the convention's sole African American attendee, argued eloquently for its inclusion, and the suffrage resolution was retained. Exactly 100 of approximately 300 attendees signed the document, mostly women.<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The convention was seen by some of its contemporaries, including featured speaker Mott, as one important step among many others in the continuing effort by women to gain for themselves a greater proportion of social, civil and moral rights, |

||

| ⚫ | The convention was seen by some of its contemporaries, including featured speaker Mott, as one important step among many others in the continuing effort by women to gain for themselves a greater proportion of social, civil and moral rights, while it was viewed by others as a revolutionary beginning to the struggle by women for complete equality with men. Stanton considered the Seneca Falls Convention to be the beginning of the women's rights movement, an opinion that was echoed in the History of Woman Suffrage, which Stanton co-wrote.<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The convention's Declaration of Sentiments became "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future", according to Judith Wellman, a historian of the convention. |

||

| ⚫ | The convention's Declaration of Sentiments became "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future", according to Judith Wellman, a historian of the convention. By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention of 1851, the issue of women's right to vote had become a central tenet of the United States women's rights movement. These conventions became annual events until the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861.<ref>https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Wikipedia}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category: Featured Articles]] |

|||

[[Category: History]] |

|||

[[Category: United States]] |

|||

[[Category: Wikipedia]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 22:43, 12 November 2023

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention and is today generally considered to be the origin of feminism by both feminists and anti-feminists, although the word itself was coined by Charles Fourier in 1837. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman". Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the town of Seneca Falls, New York, it spanned two days over July 19–20, 1848. Attracting widespread attention, it was soon followed by other women's rights conventions, including the Rochester Women's Rights Convention in Rochester, New York, two weeks later. In 1850 the first in a series of annual National Women's Rights Conventions met in Worcester, Massachusetts.[1]

Female Quakers local to the area organized the meeting along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was not a Quaker. They planned the event during a visit to the area by Philadelphia-based Lucretia Mott. Mott, a Quaker, was famous for her oratorical ability.[2]

The meeting comprised six sessions including a lecture on law, a humorous presentation, and multiple discussions about the role of women in society. Stanton and the Quaker women presented two prepared documents, the Declaration of Sentiments and an accompanying list of resolutions, to be debated and modified before being put forward for signatures. A heated debate sprang up regarding women's right to vote, with many – including Mott – urging the removal of this concept, but Frederick Douglass, who was the convention's sole African American attendee, argued eloquently for its inclusion, and the suffrage resolution was retained. Exactly 100 of approximately 300 attendees signed the document, mostly women.[3]

The convention was seen by some of its contemporaries, including featured speaker Mott, as one important step among many others in the continuing effort by women to gain for themselves a greater proportion of social, civil and moral rights, while it was viewed by others as a revolutionary beginning to the struggle by women for complete equality with men. Stanton considered the Seneca Falls Convention to be the beginning of the women's rights movement, an opinion that was echoed in the History of Woman Suffrage, which Stanton co-wrote.[4]

The convention's Declaration of Sentiments became "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future", according to Judith Wellman, a historian of the convention. By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention of 1851, the issue of women's right to vote had become a central tenet of the United States women's rights movement. These conventions became annual events until the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861.[5]

Wikipedia

This article contains information imported from the English Wikipedia. In most cases the page history will have details. If you need information on the importation and have difficulty obtaining it please contact the site administrators.

Wikipedia shows a strong woke bias. Text copied over from Wikipedia can be corrected and improved.

References

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seneca_Falls_Convention&oldid=1146284178M